Advertising Age

In early 2006, Andrew Robinson pitched a radical idea to the Doritos marketing team in a conference room at Frito-Lay’s headquarters in Plano, Texas: What if the brand held a contest to give consumers — not professional ad agencies — a crack at creating a Super Bowl ad?

The idea felt risky, new and different, recalled Mr. Robinson, who championed the concept while at The Marketing Arm, an Omnicom-owned agency that at the time was mostly handling sports marketing for Frito-Lay. But for some people in the room, outsourcing the biggest marketing move of the year to a bunch of amateurs was a bit too much to swallow, even for a brand that was looking for a bold idea to lure younger male consumers.

“There was general acknowledgment that it was big and cool,” said Mr. Robinson, now the agency’s president for consumer engagement. But “there was a lot of skepticism, as well, that the organization just wouldn’t take the risk of investing $2 million in a consumer-generated ad.”

So the pitch was rejected. But Mr. Robinson and other advocates inside Frito-Lay did not give up. They kept pushing and pitched the contest again a few months later. Top executives at PepsiCo-owned Frito-Lay finally bought it, launching what would become “Crash the Super Bowl.”

The rest is history. Crash — which is in its tenth and final year — is widely seen as a groundbreaking program that put crowdsourced ads on the map and gave Doritos a sales boost.

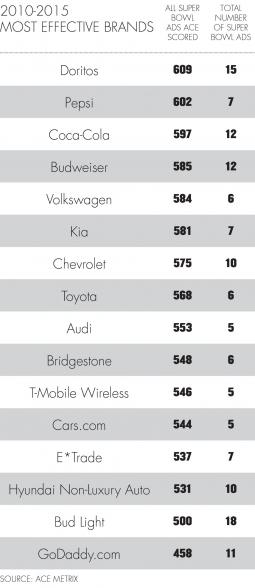

While the 21 Crash ads that have aired in the past decade are far from sophisticated — sight gags and pet tricks abound — tortilla-munching Americans seem to love them. The winning spots have earned top-five rankings on the USA Today Ad Meter every year in which they have aired, including four No. 1 rankings. Ad-scoring firm Ace Metrix ranks Doritos No. 1 on its list of the most effective Super-Bowl advertised brands from 2010-2015, ahead of Pepsi, Coke and Budweiser and other brands that typically use big-name ad agencies.

When Crash started, “a lot of people were really quite cynical and skeptical about it,” said Ace Metrix CEO Peter Daboll. But “I think it’s really proven and called into question the traditional agency model. It showed that great creative can come from anywhere.”

Frito-Lay North America Chief Marketing Officer Ram Krishnan credits Crash for helping grow Doritos from a $1.54 billion U.S. brand in 2006 to a $2.2 billion brand today. “It’s not a one-and-done deal on the game day. It’s basically this five-to six-month engagement program that we had with the consumer,” said Mr. Krishnan, who has overseen Crash since 2012. “That made it completely pay off for us.”

So why stop now? Mr. Krishnan pointed to the generational shift in Doritos’ core target from millennials to Gen Z, the label for the children of Gen Xers who are approaching their 20s. When Doritos first targeted millennials with Crash in 2006 for the 2007 Super Bowl, the media landscape was much different. YouTube was in its infancy, Twitter was barely known, the iPhone had not been launched yet and MySpace was still popular.

By turning over its Super Bowl ad to amateurs, Doritos was providing a “stage for the consumers to shine,” Mr. Krishnan. But Gen Z is “not waiting to be discovered,” he said. “They themselves are earning success by putting out their own YouTube channel and creating content for that. The role of the brand and the value that we add with this consumer has changed.”

Even so, Doritos is not giving up on user-generated content. Rather, the brand is dialing it up, but in a new format. A program launched late last year called “Legion of the Bold” holds clues as to where Frito-Lay is headed with Doritos.

The initiative involves asking the general public for creative ideas throughout the year on everything from Vine videos to banner ads. Consumers sign up via a website where they respond to frequent pitches. So far Doritos has signed up 5,000 users who have created 800 pieces of content based on 21 creative briefs, Mr. Krishnan said. Winning entrants are paid based on the complexity of the brief, he said. This Vine below is one example:

The program, if anything, is a reflection of the diminishing role of the 30-second TV spot in the digital era. “What we are doing is creating a platform that they [pitch ideas] 365 days a year instead of making this big deal about this one moment of time that we did once a year,” Mr. Krishnan said.

And in doing so, Doritos will once again bypass ad agencies, at least for creative ideas. When the brand first took that approach with Crash, it caused a stir on Madison Avenue. “Crowdsourcing something like this was totally frowned upon by the industry when we started this project out,” Jeff Goodby, whose Goodby Silverstein & Partners agency assists with promoting Crash, stated in an email interview. “It was considered a cop out, lazy, not doing our job, even timid and fearful.”

But “in time, of course, the quality of the stuff that came in for Crash got so high that success was undeniable,” he added. “The project was beating the best agencies in the world, creating the most buzz, winning the USA Today Ad Meter. You’d think that would irritate the agencies even more, but instead it somehow made crowdsourcing gradually more acceptable.”

Dawn Hudson, the National Footbal League’s chief marketing officer who has held executive roles at ad agencies and at PepsiCo, agrees. One reason that crowdsourcing is no longer as threatening to agencies is because shops still play a role, she said. “You still need people to organize it,” she said. Crash didn’t happen “because consumers decided to do it. This program happened because somebody had the idea, organized it, made it happen, provided the vehicles.” She added: “The agency world is as relevant as ever, if not arguably more relevant, as more crowdsourced individual ideas have come to pass.”

Ace Metrix’s Mr. Daboll pointed out that “we are still not seeing this abandoning of the traditional agency model. But you are seeing companies … help to enable this direct-to-producer model.” Examples of creative crowdsourcing firms include Mofilm — which has curated content for the likes of General Motors and Unilever, according to its website — and Tongal, which has secured ads for Anheuser-Busch, Procter & Gamble, Lego,General Mills, Bacardi and others.

In the case of Crash, the cost of crowdsourcing a Super Bowl spot is about on par with securing an ad via an agency, according to a brand spokesman. While Crash has been tweaked over the years, the general structure remains the same: Doritos takes submissions beginning in the fall. The brand selects finalists and consumers vote on which ad will run in the Super Bowl. In some years, Doritos execs have picked an additional spot to run. This year, only one ad will air.

In the early days, one of the brand’s biggest fears was ensuring it had the bandwidth to handle all of the submissions, recalled Jason McDonell, who was an early advocate for Crash while serving as the senior marketing director overseeing Doritos in 2006. Ads poured in right at the deadline because people didn’t want to give away their ideas to others. “The last 12 hours were a bit unnerving,” said Mr. McDonell, currently the president of PepsiCo Foods Canada. The winning ad that first year, “Live the Flavor,” (below) earned a No. 4 ranking in the Ad Meter, bolstering Frito-Lay’s case to keep the program running.

Entrants often have some filmmaking experience but are looking for their first big break. They are people like Mark Freiburger, whose ad, “Fashionista Daddy,” aired in the 2013 Super Bowl.

Mr. Freiburger, who was age 29 when he entered, had previously never made a commercial, although he had two small independent films to his credit, he said. He was enticed to enter Crash by that year’s prize: the chance to work with director Michael Bay on the next installment of the “Transformers” movie franchise.

He shot the Doritos ad in eight hours, using a friend’s house as the setting. It only cost $300 to make, he said. “We got just a bunch of friends to come out and everybody brought equipment and donated their time,” he said.

The ad ended up raking No. 4 on the Ad Meter, putting it ahead of professionally produced spots for the likes of Coke, Pepsi and Toyota. Mr. Freiburger’s spot consisted of a group of dads dressing up like princesses as a way to gain access to a young girl’s bag of Doritos (below). It was, like all Crash ads, not exactly highbrow stuff. And that’s kind of the point.

It’s “not rocket science,” Mr. Freiburger said. “You have to think about what your audience is for the Super Bowl, which is massive groups of people sitting around eating food together … and people drinking beer in loud environments,” he added. “They want to laugh. They want goofy. They want over-the-top.”

For the past 10 years, Doritos gave viewers exactly that.

View the original article on AdAge