It’s fitting that we publish the next iteration of our Celebrity Paper on the eve of the Super Bowl. Come Sunday, we will see more than two dozen famous folk in the 40+ ads that will run during the game. If history serves as a guide, the ads featuring celebrities will underperform those without the glitterati – as they have in every Super Bowl we have data on.

The question is why? Why don’t celebrities bring their fame and fortune to the brands they endorse? The answer is complex and requires some pretty slick math to truly grasp, but the short answer is this; celebrities are often a poor fit for what they are endorsing and are often a weak substitute for better creative and more comprehensive testing of creative concepts. Even when they do work, the return on investment associated with employing them is bleak, at best. To fully answer this question, we have now made available, free to you, our latest whitepaper, The Impact of Celebrities in Advertising.

Let’s be clear. The first paper we wrote – 18,000 ads ago – and the one we published today don’t suggest that ads can’t succeed with celebrities – ads absolutely can succeed with celebrities and the paper calls out those celebrities whose portfolio of work is notable. What this paper says (confirming the data in the previous paper) is that the odds are stacked against the advertiser.

The ones that succeed do so with a blend of persuasive messaging and authenticity. There is a clear reason why the celebrity was featured in the ad, a connection, if you will. Alternatively, unsuccessful commercials frequently paired a celebrity with a product or brand where there was no clear connection between the two. In many cases where this occurred, it seemed as though the advertiser was keen on featuring a celebrity, not necessarily one that fit the purpose of their communication.

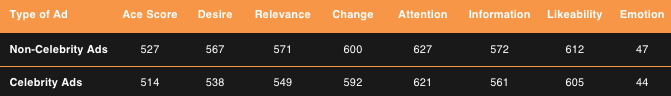

At the most basic level, here is what the data tells us:

But there is more to the story and that’s what makes the paper such an interesting read. We know from our database of over 30,000 ads that some industries score better than others. Casual Dining delivers scores in the 600s – everybody likes a good steak shot. Financial Services delivers scores in the high 400s – because not everyone needs a reverse mortgage or a more powerful trading platform. That is why we set norms by industry, category or sub-category, because context matters. Context extends to demographics as well. While the aforementioned Casual Dining category is broadly targeted, Personal Care is not as general, shaving cream spots skews male while cosmetics ads skew female.

These systemic biases should be accounted for and that is exactly what our resident PhD, Michael Curran, did in his model. Michael created an analytic plan that (a) models the targeted creative score as a function of both the advertisement’s industry as well as an indicator of whether the ad featured a celebrity or not and (b) models the highest creative score by demographic—a proxy for the demographic campaign target.

The random effects model he employed means that controlling for both Industry AND demographic reveals the “pure celebrity” effect. In essence, the model gives a celebrity every benefit of the doubt by controlling in terms of targeted demographic (picking the highest of the six age/gender demos) and industry bias. Even with these advantages, celebrity advertising can only muster a 3.7-point advantage over standard, celeb-free advertising. That accounts for four-tenths of a percent benefit from having a celeb in your ad. While celebrity endorsement price tags vary greatly, they are not free, which is likely the price they would have to be to post up any reasonable ROI for their inclusion.

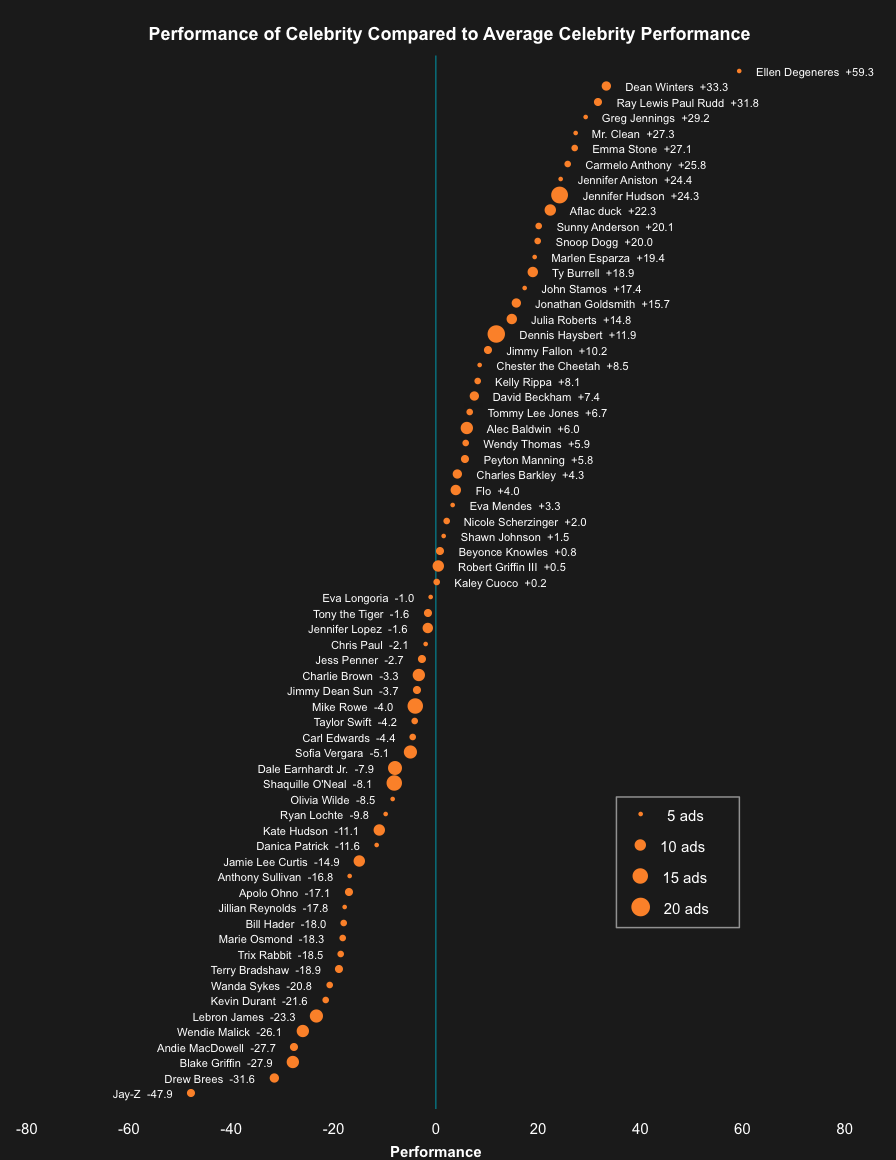

Still, what fun is PhD level statistics without a list or two? Recall that the average performance lift, in general, is a mere 3.7 points, thus each point depicted is a deviation above or below 3.7. In addition, the size of the points indicates the number of ads (i.e., the basis) for each celebrity’s average performance. Thus, this chart identifies both the average performance by celebrity as well as the volume of commercials that comprise that mean.

This is the “pure celebrity” effect on full display. Ellen gets to wear the shiny crown – dethroning Ms. Winfrey (the last paper’s winner) in this installment of celebrity endorsers. Dean Winter’s collection of Mayhem ads for Allstate also performs well, as does Ray Lewis and Paul Rudd, known for their approachable Playstation ads. We also threw some mascots onto the list. Mr. Clean tops the list (consistent with other, albeit less scientific data), and the Aflac Duck has a positive impact too. Stay tuned for another installment that isolates these franchise characters using a similar methodology. Download the paper for the full list.

The celeb performance is made up of individual ads, and we detail that in the paper too. Olympic darling Jordyn Wieber snags three spots in the top ten while galactic superstars LeBron and Jay-Z post up in the bottom ten. The full list is in the paper.

Last but not least, and another reason to keep checking back with us, is the upcoming Celebrity Calculator. That’s right, a Bayesian model that will predict the success or failure of any pairing of celebrity and brand, including hypothetical ones that have never actually occurred. It came out of the research and Dr. Curran is putting the finishing touches on the Celebrity Calculator. More science and technology from your friends at Ace Metrix.

Again, the paper is an approachable, fascinating read. If, after reading it, you want to get granular, reach out to us at creative@acemetrix.com, and we can put together a call Dr. Curran to dive deep into the methodology.